A’s Achieved by Anyone

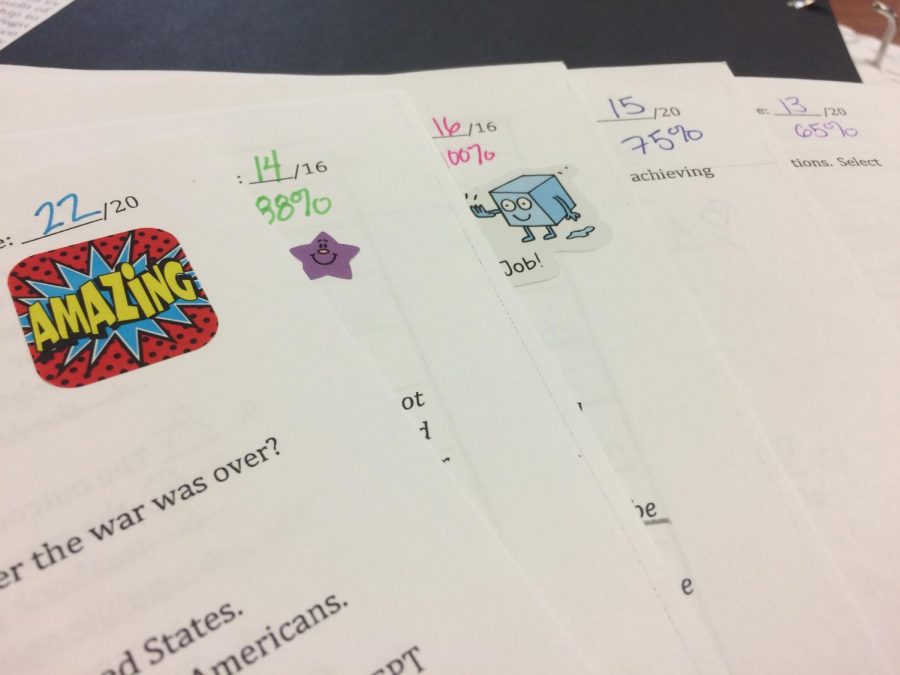

One students quiz scores from the past few months.

Bad grades are equal to failure in many teens’ minds, making school a high-stress environment, but the pressure is not just on teens to get good grades, it is on schools and teachers to have overall good ratings. This phenomena leads to one thing: grade inflation.

By definition, grade inflation, taken from the economic term of inflation, is awarding higher grades to students to raise an average. It is also the awarding of a higher grade that, in the past, would not have been given for the same work. But how did this come about?

In the 19th century, Yale was the first education institution in the United States to have a grading method similar to what all American schools use today. They recorded students grades in a Book of Averages, similar to modern-day 4-point grade point average scales. Then, in the late 19th century, universities began to experiment with letter grades. In the early 20th century, standardized grading systems moved to high schools due to the increasing number of students attending school. Large variability between teachers led many to want an even more standardized grading system, leading to the modern-day system. Then, during the Vietnam War Era, grade inflation began in colleges. Students with high grades, usually A’s and B’s, could be exempt from the draft. Teachers did not want to be the reason their students were sent to war, so they tried to give them higher grades. Since that time, grade inflation has continued.

Students in the halls of Rochester Adams High School.

Today, some teachers use better grades as an incentive for good behavior, while others are pressured by their administration or even parents and students for better results. In the 2017 school year, only 31% of 8th grade students in Michigan were at least proficient in math, and 34% were at or above proficient in reading according to standardized test scores. Meanwhile, 98% of Michigan teachers that same school year were reported as either effective or highly effective in their teacher evaluation ratings.

“The definitions attached to each of the four ratings are locally-determined by the district for the system of evaluation that is in place. In other words, there is not currently a standard, statewide definition of each rating…So, what is ‘effective’ in one district may not be equivalent in another district,” said the 2012 “Educator Effectiveness Ratings FAQs” put out by Michigan’s government.

These non-standardized assessments allow districts to create their own standards, and, as education is a business, allow principals to be lenient with teacher assessments to attract families and awards. According to edweek.org, principals continue to report teachers as effective in evaluations, while in confidence they admit some of those teachers are not. Many principals want to maintain good relationships with their teachers, and often a bad evaluation hurts that relationship, so instead principals give favorable assessments. Some students even believe that grade inflation is morally wrong.

“Grade inflation does not make sense and ultimately is not fair. People who get the extra grade think it is good for them but other people who don’t receive the grade too think it is unfair,” said freshman Josie Eckman.

Grade inflation also has a negative impact on students. The easier grades that teachers give allow students to do less work and still get good grades. In a article from the74milion.org, one teacher explains the pressure from administration to give students extra chances to get good grades, creating an expectation among students that deadlines are not really deadlines and that little effort still means a good grade. The extra chances given to students makes more work for already overworked teachers to grade. Not only do teachers feel more pressure from grade inflation, students do too.

“I feel it is very much at least Adams culture to be obsessed with keeping the highest grades and taking the most advanced classes to get into the best college. There is a lot of pressure from parents and peers in this area to be the best, most successful student, which fosters ambition but also creates unnecessary self doubt and anxiety,” said junior Anna Jackson.

Revaa Goyle taking notes in one of her classes.

Though grade inflation seems to be the result of a corrupt, self-preserving, heartless education system, it really is not. When teachers give better grades, they empower their students, not just in the classroom, but also in other situations.

“Through my grades, I know I put as much effort in as possible and I have constant faith that in the end, the result will show that I did try my best. That makes me feel I am prepared and dedicated as a student. Although, I know I do try my best no matter what, receiving good grades helps boost my self-esteem and lets me know I have worked for what I got,” said sophomore Isabella Boiani.

These inflated grades also help students after they graduate college. Recently, more and more colleges have significantly lowered the number of C’s given out, thus dramatically increasing the average GPA. Schools with higher GPA averages due to grade inflation have more students accepted to more prestigious graduate and doctorate schools, whereas some schools that try to prevent grade inflation hurt their students chances at the same schools and universities their equally skilled opponents are accepted to.

Unfortunately, there is no solution to this issue. If we try to reverse grade inflation, we ignore how it has helped many students and how other student would be furious. There is no way to make grades equally inflated as all teachers are different and grade differently.

In the end, grades are just a measure of a student’s academic performance, they do not measure someone’s talents and worth. A’s and B’s may help or hurt an individual’s chances of getting into certain colleges, but there are other colleges and opportunities to learn that do not require perfect grades. So, does an inflated grade really matter as long as students are learning?